This country is where you can find some of the world’s rarest animals

- Aegean Islands Promo

-

Feb 08

- Share post

IN THE ISLAND forests of the western Pacific, there’s an otherworldly animal known as the Philippine tarsier.

With bat ears, suction cup–like fingers, and giant golden eyes, the creatures would be easy to mistake for extras on a sci-fi movie set. But in fact, tarsiers are primates and distant relatives of humans.

“They really look like little aliens jumping from tree to tree,” says Gab Mejia, a National Geographic Explorer and photographer based in the Philippines.

The Philippines’ 7,600-plus islands are the cradle for a mind-boggling number of diverse species. According to the Convention on Biological Diversity, 5 percent of the world’s plant species live in the Philippines. And nearly half of the creatures found on these islands exist nowhere else.

The morning sun paints the mountain highlands of Bukidnon, home to the rare Philippine eagle.

PHOTOGRAPH BY GAB MEJIA“Everywhere you go in the Philippines, you’re going to be surrounded by nature,” Mejia says. “Each island you travel to will have different species.”

Island living tends to encourage speciation—or the divergence of one species into two or more lineages. But this ecological paradise is also under attack, with more than 700 of its native species considered threatened by extinction, as a result of overharvesting, habitat loss, and habitat fragmentation. And the global pandemic may be making things even worse, as conservation organizations have noted upticks in both illegal fishing and poaching of rare plants.

The good news is that, in recent years, home-grown efforts to save many of these creatures and their habitats have proliferated. And when it is done sustainably, biodiversity tourism at national parks can help boost these efforts by channeling money to local conservation groups, ensuring that they have enough support to fund patrols, buy tracts of land, and even breed rare species in captivity.

COVID-19 has put a damper on travel, but once it’s safe, conservation-minded travelers can discover these four national parks in the Philippines that host four of the rarest yet charismatic wildlife found only here.

Tarsiers: small and ultrasonic

The Philippine tarsier is the world’s second smallest primate and has been known to Western scientists since it was first described way back in 1894. But one aspect has remained a mystery until recently.

Philippine tarsier range (Carlito syrichta)

South

China

Sea

Philippine

Sea

Luzon

Manila

Samar

PHILIPPINES

Philippine Tarsier and

Wildlife Sanctuary

Leyte

Bohol

Bohol

Sulu

Sea

Mindanao

150 mi

150 km

MALAYSIA

KATIE ARMSTRONG, NG STAFF.

SOURCE: IUCN RED LIST

On some occasions when a researcher would pick up one of the candy bar–size primates, the animal would open its mouth wide as if it were howling, but no sound would come out. The behavior was considered espeically weird because the species was already known to produce a handful of other audible vocalizations, including a piercing shriek and a soft trill that sounds like bird song.

The mystery was solved in 2012 when scientists revealed that the Philippine tarsier actually communicates in ultrasound, or sound frequencies so high they exceed human hearing. The tarsiers’ stress-induced screams weren’t silent after all; they were simply akin to a dog whistle.

Amazingly, tourists can actually catch a glimpse of these near-threatened, nocturnal primates in the wild—if they know where to look.

A Philippine tarsier perks up at the sound of a hidden insect moving among the leaves of a forest in Bohol. The tarsier’s hearing abilities are more acute than any other primate.

PHOTOGRAPH BY GAB MEJIA“At night, they go out to hunt, but afterwards they go back to the same tree,” says Mejia.

Sadly, this consistency also puts the animals at risk, because those who might want to snatch the critters up for food or the pet trade can find them rather easily.

The key to seeing the animals without disturbing them is to book the right guide. Mejia recommends the Philippine Tarsier Foundation, which runs the Philippine Tarsier and Wildlife Sanctuary on the island of Bohol.

Tamaraws: mighty but mini

Filipinos consider the tamaraw to be one of the most popular and cherished animals on Earth. But outside of the islands, most people have never even heard of the Philippines’ only native bovine species, a mighty-but-mini water buffalo, of sorts.

Tamaraw range (Bubalus mindorensis)

Manila

AREA

ENLARGED

PHILIPPINES

Mounts-Iglit Baco

National Park

Mindoro

Strait

50 mi

50 km

KATIE ARMSTRONG, NG STAFF.

SOURCE: IUCN RED LIST

The tamaraw is found only on the island of Mindoro. The species sports shiny black hair, backward-facing horns, and a height no taller than a kindergartener. But don’t let its lack of stature fool you. The animals have famous tempers and will readily wield their horns against intruders, a behavior called “tusking.”

“They’re really wild animals,” says Mejia. “Rangers have told me about getting chased up trees by them, and what you’re supposed to do is jump sideways, because they charge blindly.”

This 2018 photo shows Kalibasib, the only remaining tamaraw in captivity, inside the Tamaraw Gene Pool Farm in Mindoro Province. The Tamaraw Conservation Program employed tribesmen as trackers and forest rangers, leading to a decrease in poaching.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JES AZNAR, GETTY IMAGESUnfortunately for the fierce little bovines, the animals’ meat is still prized by some hunters, and diseases from cattle and other livestock have hit the species hard. The International Union for Conservation of Nature considers it to be critically endangered; only 600 individuals remain in the wild.

“Visitors can see them in the wild, though, in Mounts Iglit-Baco National Park,” says Neil Anthony del Mundo, coordinator of the Tamaraw Conservation Program.

Of course, tamaraws should only be observed from a safe distance.

Philippine crocodiles: world’s rarest

The Philippine crocodile is the rarest crocodile in the world, and yet visitors to Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park have a good chance of seeing these animals in their native habitat. The only catch? You have to bring a headlamp.

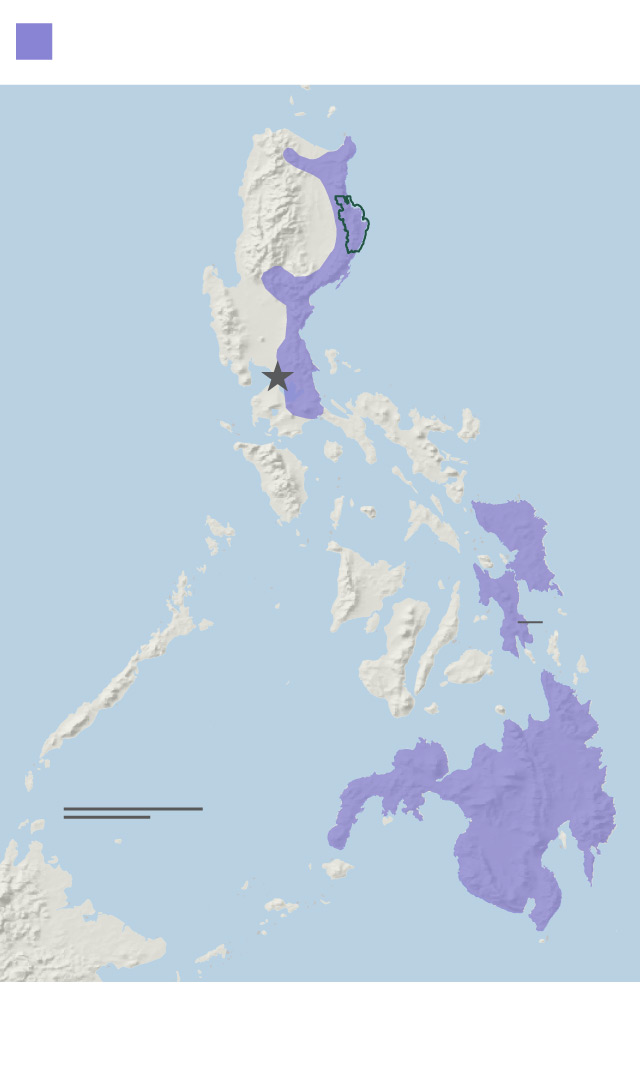

Philippine crocodile range

(Crocodylus mindorensis)

Northern Sierra

Madre Mountain

Range Natural Park

South

China

Sea

Philippine

Sea

Luzon

Manila

PHILIPPINES

Sulu

Sea

Mindanao

150 mi

150 km

MALAYSIA

KATIE ARMSTRONG, NG STAFF.

SOURCE: IUCN RED LIST

“We have built an observation tower on the edge of a natural lake where we can almost guarantee seeing Philippine crocodiles at night,” says Merlijn van Weerd, CEO of the Mabuwaya Foundation, a conservation nonprofit.

Like the tamaraw, the Philippine crocodile is on the smaller side of the spectrum, with mature animals reaching around five feet in length and just over 30 pounds. In fact, the croc’s favorite food is snails.

These include invasive golden apple snails, which are a threat to local rice farmers, says van Weerd. Philippine crocs also enjoy gulping down introduced rats, another crop pest.

Amante Yog-yog, crocodile specialist, examines the protruding scales in the neck of the juvenile Philippine crocodile. The existence of scales in the neck are the main physical feature in determining whether the species is a Philippine crocodile or a saltwater crocodile.

PHOTOGRAPH BY GAB MEJIA“So endemic Philippine crocodiles are helping Philippine farmers by controlling introduced pest species in their rice fields,” says van Weerd.

With between 92 and 137 mature Philippine crocodiles left on Earth, the critically endangered species needs all the good PR it can get. And, unfortunately, people do sometimes kill the reptiles because they see them as a threat to livestock or even people.

Philippine eagles: unlike any other

With creamy white underbellies and an unmistakable crown of shaggy feathers, a Philippine eagle makes a regal impression. “When they stretch their wings, it covers everyone in shadow,” says Mejia. “They’re like the kings or queens of the raptors.” No wonder then that the species was named the Philippines’ national bird.

Philippine eagle range

(Pithecophaga jefferyi)

Northern Sierra

Madre Mountain

Range Natural Park

South

China

Sea

Luzon

Philippine

Sea

Manila

Samar

PHILIPPINES

Leyte

Sulu

Sea

Mindanao

150 mi

150 km

MALAYSIA

KATIE ARMSTRONG, NG STAFF.

SOURCE: IUCN RED LIST

While these avians, also known as monkey-eating eagles, are difficult to find in the wild, where no more than 400 adult pairs remain, it is still possible to see the species in captivity.

“Since the program began during the 1970s, we have rescued 86 eagles,” says Jayson Ibanez, director of research and conservation at the Philippine Eagle Foundation.

Reasons for rescue include trapping and shooting by locals, but the main factor afflicting the species is deforestation. A single breeding pair requires between 10,000 and 27,000 acres for its home range, as well as tall trees for nesting. At the same time, just 35 percent of the Philippines’ forests remain intact.

The foundation also currently houses 33 Philippine eagles. Through breeding attempts, the staff hopes to release new chicks into the wild.

A Philippine eagle roosts in the forest sanctuary of the Philippine Eagle Foundation, in Davao. With only about 400 pairs left in the wild, Philippine eagles are rescued, bred, and released back to their mountainous habitats, such as Mount Apo National Park.

PHOTOGRAPH BY GAB MEJIAInterestingly, it was once thought that this species was related to other large forest eagles found around the world, such as the harpy eagle of South America and the crowned hawk eagle of Africa. But DNA studies have since revealed that those other large-bodied birds are only distant relatives; the Philippine eagle is in a category of its own.

“They are unique products of evolutionary creation,” says Ibanez.

Of course, uniqueness seems to be a theme echoing across this magnificent archipelago.

“The Philippines really are shaped by islands, mountains, and wetlands,” says Mejia. “Whether it’s a monitor lizard on the beach or a tarsier in a tree, be prepared to really see what it means to be a mega-biodiverse country.”

RELATED: 50 ANIMALS IN PERIL

Normally found in the evergreen and semi-evergreen forests of Vietnam, Laos, and China, the endangered northern white-cheeked gibbon has nearly disappeared from the wild.

Source: nationalgeographic.com/travel